What Is Miniature Painting?

What is miniature painting, fundamentally? It's a painting technique combining extraordinary detail work, natural materials, and meticulous execution on a modest scale - though "modest" here is misleading because some works measure larger than expected. The defining feature isn't size but approach: the artist works at close range, often with magnification, using brushes finer than modern sensibilities typically imagine, layering pigments so thin they become translucent.

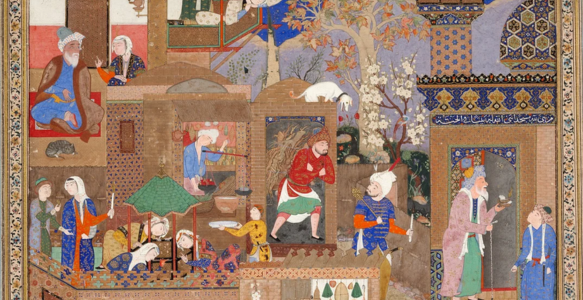

The flattened perspective is deliberate. What are miniature paintings, if not a rejection of Renaissance realism in favor of spiritual and decorative intensity? Figures remain stylized rather than anatomically accurate. Space collapses. Gold leaf catches light. Color stays local - a red stays vivid red rather than shadowing toward brown. This flatness is a choice rather than a limitation rooted in centuries of artistic conviction that beauty lives not in illusion but in the intensity of the surface itself.

The surfaces themselves tell a story. Vellum, ivory and handmade paper prepared with meticulous care. A single miniature painting might consume months of an artist's life - sometimes multiple artists collaborated, each specializing in portraiture or gold work or botanical detail. The commitment of labor and materials reflects a belief that some things deserve to be made slowly, expensively, perfectly.

History of Miniature Painting

1. Origin of Miniature Painting

The origin of miniature painting reaches back to 7th-century Bengal, where Pala dynasty monks needed illustrated Buddhist texts for spiritual teaching and meditation. Palm leaf manuscripts, constrained by their narrow width, became canvases for intricate illustration. These weren't elaborate by later standards, but they established something fundamental: the principle that small spaces could hold spiritual significance. By 999 AD, the Prajnaparamita manuscript demonstrated the refinement already achieved. Subdued colors. Sinuous lines influenced by Ajanta murals. A technique already mature before the rest of the world recognized it as a distinct art form.

Jain manuscripts followed. The Kalpasutra folios of the 10th-14th centuries show how the origin of miniature painting extended beyond Buddhism into other religious traditions. Each region developed its own character, but the impulse remained constant: make the sacred visible, portable, intimate.

What's often overlooked is how this Indian tradition developed largely independently before encountering Persian influence. The Pala artists weren't copying anything imported. They were inventing something new out of necessity and devotion.

2. Persian Influence on Miniature Art

Persian miniaturists cultivated a parallel sophistication - though in Persian courts rather than Buddhist monasteries. The Timurid dynasty (14th-15th centuries) and later the Safavid empire (1501-1736) produced manuscripts of breathtaking refinement. Herat, Tabriz, Isfahan were centers of connoisseurship where the miniature form became intimately connected to court culture, library collections, and the cultivation of taste among refined patrons.

The Safavid synthesis - merging restrained Herat aesthetics with expressive Tabriz intensity - established principles that would ripple across the Islamic world. Masters like Kamaliddin Behzad set standards of precision and compositional sophistication that became reference points for artists working centuries later. These weren't illustrations in the modest sense. They were independent artworks, collected in albums (muraqqa) meant for private study.

What's crucial: Persian and Indian traditions evolved separately, then encountered each other. The Persian influence on miniature art arrived not as conquest but as exchange. Mughal emperors actively recruited Persian artists, learned from Persian techniques, then synthesized something distinctly their own.

3. Development of Miniature Painting in India

The development of miniature painting in India accelerated dramatically under the Mughal Empire. Akbar (1556-1605) commissioned approximately 1,400 illustrations for the Amir Hamza epic - an unprecedented scale that established miniature painting as a central imperial art. The technique absorbed Persian delicacy, Indian boldness of color, and eventually European influences brought by Jesuit missionaries familiar with works by Dürer and others.

Jahangir (1605-1627) inherited this tradition and refined it toward something almost scientific. Portrait studies. Botanical illustrations of stunning accuracy. The artist Ustad Mansur captured specific bird species with such precision that these paintings functioned as natural history records. Miniature painting history becomes, in Jahangir's reign, the history of how imperial patronage transforms technique into something approaching obsession with accuracy and beauty simultaneously.

Beyond the Mughal court, regional schools flourished. Rajasthani kingdoms developed their own aesthetic. The hill kingdoms produced the ethereal Kangra tradition. Each school represents the development of miniature painting in India as an ongoing conversation between regional identity and imperial influence, between received tradition and local innovation.

Key Characteristics of Miniature Art

The following section offers essential miniature painting information, outlining the materials, scale, tools, and techniques that define the tradition across regions and centuries.

1. Size and Scale

Most miniatures occupy no more than 25 square inches, though the largest Mughal examples - those epic illustrations - measured 22 by 28 inches. What remains consistent is the method. The artist worked in proximity. Details were rendered at approximately one-sixth actual size. This created an optical experience fundamentally different from larger paintings. You don't view a miniature, you actually enter it.

2. Natural Materials

Lapis lazuli imported from Afghanistan - a stone prized for 4,000 years - ground to powder creates the blues. Vermillion. Ochres. Siennas. Umbers. Blacks from lamp soot or burnt bone. These weren't industrial pigments but natural substances requiring preparation, testing, sometimes weeks of grinding and washing to concentrate the hue.

The binders mattered equally. Egg white, Gum Arabic, Fish glue are key here. These held pigment particles together, allowing adhesion and luminosity impossible with modern synthetic alternatives. Gold and silver leaf - sometimes applied as genuine metal, sometimes as suspension in liquid - transformed paintings into objects of literal luminosity. The commitment to natural materials extended beyond practicality into philosophy: these substances connected the artist to the earth, to history, to permanence.

3. Fine Tools

Brushes composed of selected animal hair - sable, marten tail, squirrel - bound with meticulous care. Not the single-hair mythology, but refined multi-hair implements capable of extraordinary sensitivity. A master's collection included dozens of sizes and shapes, each reserved for particular tasks. Some artists modified their own brushes, calibrating them to personal technique.

Burnishing tools mattered equally. Smooth stones - agate, local golla - used with gentle pressure to compress paint layers and reflect light. This process transformed a finished painting from matte to glowing, creating the enameled quality characteristic of the finest historical examples.

4. Surfaces

Palm leaves gave way to vellum - treated animal skin from calves, kids, lambs - stretched, sized, sometimes primed with gesso. They were expensive, durable and superior to paper. By the 17th-18th centuries, prepared papers became common, particularly Sialkoti paper in the Kangra tradition - handmade from cotton and bamboo, burnished with river stones to achieve requisite smoothness.

Around 1700, ivory began displacing vellum, offering natural luminosity that enhanced transparent watercolors. The oily surface created technical challenges; pigments didn't absorb but remained on the surface, requiring modified application techniques. Yet the aesthetic payoff - the glow that ivory provides - made it the preferred surface for portrait miniatures through the 19th century.

5. Intricate Details

This is where a miniature painting approaches something almost mystical. The level of detail achievable borders on the obsessive. A six-inch-by-three-inch composition might contain dozens of figures, each with distinct features. Feathers rendered individually. Tiles on palace floors precisely delineated. Flowers in margins varied and specific. Not detail for its own sake - every element contributes to meaning, conveying status, emotion, narrative significance.

Layering was essential. Preliminary sketches in line. Base colors in broad washes. Then gradual building of detail through successive applications, each allowed to dry before the next. This methodical approach required sustained focus and what amounts to a meditative discipline.

Types of Miniature Painting Styles

1. Mughal Style

Mughal miniature paintings history represents the most technically accomplished synthesis achieved: Persian elegance plus Indian intensity plus European influences. Meticulous realism combined with jewel-toned color and flattened perspective. Narrative clarity. Naturalistic animals and botanical elements rendered with scientific precision, yet the overall effect remains decorative rather than photographic.

The Amir Hamza illustrations depict dramatic scenes of combat and magic. Jahangir's nature studies approach scientific documentation. Court scenes capture imperial ritual with precise attention to hierarchy and costume. Gold and silver leaf create luminous accents emphasizing the precious quality of the object itself.

2. Rajasthani Style

Rajasthani schools - Mewar, Marwar, Bundi, Kota, Kishangarh - developed parallel to Mughal dominance. Beginning with Jain manuscript traditions (15th century) and flowering through the 18th-19th centuries, these schools privileged stylization over realism and practices emphasizing devotional intensity over courtly splendor.

The Krishna-Radha narratives from the Gita Govinda became primary inspiration. These paintings vibrate with color and emotional intensity, depicting intimate moments and psychological states rather than public events. The Kishangarh school achieved an extraordinarily stylized approach - elongated faces with pointed chins, large almond eyes, sinuous bodies floating on the page. Court painter Nihhal Chand developed this refined aesthetic under King Savant Singh's patronage. Bundi and Kota schools emphasized genre scenes - hunting, courtyard gatherings, domestic moments - with attention to landscape and architectural detail.

3. Pahari Style

The hill kingdoms of the northwest - Himachal Pradesh, Jammu - developed perhaps the most poetic tradition. Emerging in the 17th century and reaching its apex in the 18th and early 19th centuries, Pahari miniatures are celebrated for ethereal quality and sophisticated landscape integration.

The Kangra school, developed under Maharaja Sansar Chand's patronage in the late 18th century, represents the pinnacle. Delicate lines applied with brushes of extraordinary fineness. A pale palette of soft pinks, yellows, blues, greens creating luminous, ethereal effects - quite different from the jewel-toned intensity of Mughal or Rajasthani work. The subjects remain consistent - Krishna-Radha narratives, Bhagavata Purana scenes, Sanskrit literary themes - but treatment emphasizes psychological and spiritual states. These are paintings of longing and devotion, rendered through landscape and color as much as figural representation.

4. Deccan Style

Deccan miniatures developed in sultanates of central and southern India - Bijapur, Golkonda, Ahmadnagar, later Hyderabad - during the 16th-18th centuries. A distinct synthesis: Persian influence, Mughal realism, indigenous Indian aesthetics resulting in something more lyrical and expressive than Mughal work, more dynamic than many Rajasthani examples.

Characteristic softness combined with bold, saturated color. Elongated, graceful figures. Dreamy, fantastical landscapes. Romantic intensity rather than documentary precision. The Hyderabad school, emerging in the 18th century under the Asaf Jahi dynasty, continued this tradition while incorporating Mughal influences, creating works of considerable sophistication depicting courtly life, royal portraiture, and Ragamala paintings.

5. Persian Style

Persian miniatures, while not Indian, profoundly influenced subsequent traditions. The Safavid synthesis united Herat's classical restraint with Tabriz's vivid expressionism, valuing finesse of line and sophisticated spatial layering. Compositions often depict literary scenes - passages from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) - rendered with both narrative clarity and poetic subtlety.

Technical approaches differed somewhat from Indian practices. Persian painters often worked in opaque watercolor (gouache) and liquid gold on prepared paper, building through careful layering. Compositions employed "floating space" - figures arranged without strict linear perspective, creating flattened, almost abstract spatial effects prioritizing decorative harmony over naturalistic representation.

FAQs About Miniature Painting

1.Where did miniature painting originate?

Miniature painting originated in India during the 7th century AD under the Pala dynasty in Bengal, where Buddhist texts were illustrated on palm leaf manuscripts. Simultaneously, Persian traditions of manuscript illumination developed through the medieval period, eventually synthesizing under the Safavid dynasty into a refined courtly art. Both traditions would eventually meet when the Mughal Empire brought them into contact during the 16th century.

2.What is the oldest miniature painting?

The earliest securely dated miniature manuscript is the Prajnaparamita manuscript of 999 AD, illustrated on palm leaf. This tradition continued and diversified, with Jain Kalpasutra manuscripts from the 10th–14th centuries among the most celebrated surviving examples.

In the Persian tradition, miniature painting emerges later, most notably in Timurid manuscripts of the 14th–15th centuries.

3.What are the main features of miniature paintings?

Essential features include: intricate detail rendered through fine brushwork; natural materials - mineral and earth pigments, animal hair brushes, surfaces of vellum, ivory, or prepared paper; luminous color achieved through layering and burnishing, often enhanced with gold and silver leaf; flattened perspective and stylized forms; thematic content drawn from mythology, devotional literature, courtly life, or natural observation; and intimate scale designed for close viewing and private contemplation.

4.Which country is famous for miniature painting?

India is most celebrated, particularly during the Mughal period (16th-19th centuries) and through regional schools of Rajasthan and the Himalayan foothills. However, Persia developed an equally sophisticated tradition, particularly under the Safavid dynasty. The Indian and Persian traditions were constantly in dialogue - Mughal miniaturists drew from Persian masters while later schools incorporated Mughal innovations. India's prominence partly reflects which traditions survived; Indian courts continued the form into the 19th century, long after Persian examples had declined. Contemporary collectors exploring indian art online discover both traditions well-represented.

5.What themes are commonly shown in miniature paintings?

Common themes include: devotional narratives, particularly the Krishna-Radha romance from the Gita Govinda; mythological epics, especially Ramayana and Mahabharata scenes; literary narratives like Nala-Damayanti; Ragamala and Baramasa cycles translating musical modes and seasonal emotions into visual form; courtly scenes depicting durbar, hunts, and garden gatherings; botanical and zoological studies; portraiture, especially royal subjects; and spiritual themes emphasizing psychological and emotional states. Artists working paintings of south india traditions often adapted these classical themes into regional aesthetic languages. Those drawn to folk paintings traditions will find related but distinct visual vocabularies. For devotional imagery, buddha paintings collections trace ancestry directly to Pala Buddhist manuscripts. Even office paintings collections occasionally include contemporary interpretations of classical miniature aesthetics.