What is Madhubani Painting?

Madhubani art is a traditional folk painting style originating in the Madhubani district of the Mithila region, spanning Bihar in India and parts of Nepal. It is a women's art form, though the precise designation has always been more complicated than that - shaped by caste, region, and history. What makes Madhubani painting distinctive is not a single technique but rather a philosophy of composition: absolute density, symbolic saturation, and the conviction that visual richness carries spiritual weight.

For readers looking for madhubani art information beyond a surface definition, the clues are in the materials and the rules: natural pigments, ritual contexts, and a compositional discipline that refuses emptiness.

The paintings are created using natural pigments derived from plants, flowers, and minerals. Traditionally, artists worked on mud-plastered walls and floors, using fingers, twigs, bamboo pens, cotton rags, and matchsticks as tools. Modern practitioners now work on paper, canvas, and fabric, using both traditional natural pigments and contemporary acrylics and watercolors. Seen this way, Madhubani belongs firmly to the lineage of handmade paintings - works shaped by touch, repetition, and embodied knowledge rather than mechanical reproduction. The layering of pattern, the doubling of lines, the filling of every space with intention: these are meditative acts, practices of presence.

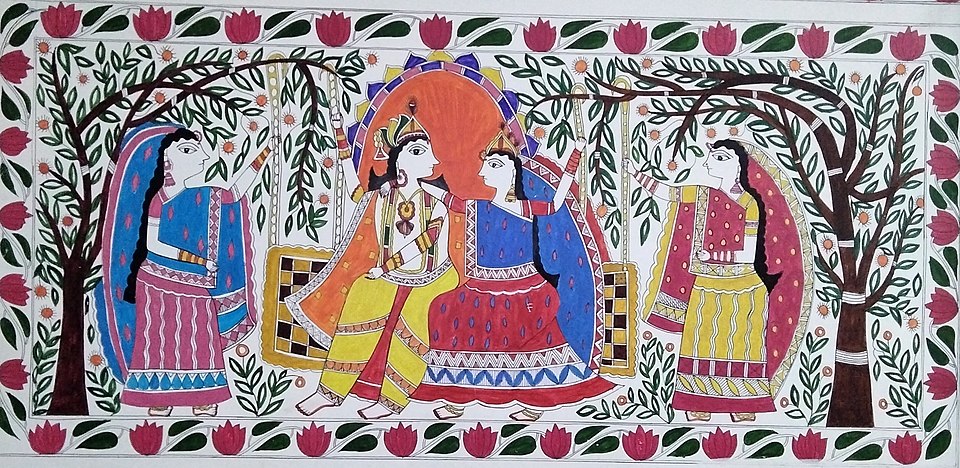

The paintings often depict scenes from Hindu mythology (Radha and Krishna, Shiva and Parvati, Durga, Lakshmi, Ganesha), nature (fish, peacocks, elephants, lotus flowers, bamboo), and social events (weddings, births, festivals). This isn't maximalism for its own sake - it's a belief system. In the Mithila cosmology, emptiness is inauspicious and fullness is blessing.

History and Origin of Madhubani Art

1. Historical Background of Madhubani Art

The history of Madhubani begins in mythology and legend, which is where so much of this region's history actually lives. According to tradition, this art form emerged in the ancient city of Mithila, the birthplace of Sita, daughter of King Janak. The legend holds that when Sita was to be married to Lord Rama, King Janak commissioned the most skilled painters to embellish his palace with paintings commemorating this marriage.

Whether or not this legend holds strict historical truth, it establishes something crucial: Madhubani was always tied to blessing, to ritual, to the consecration of significant life events. Weddings. Births. Festival times. This was the original context - not gallery walls.

What we know more concretely is that Madhubani painting developed over centuries within the Mithila region as a living tradition, transmitted orally and through practice from mothers to daughters, grandmothers to granddaughters. It was identified by caste groups in complex ways - Brahmin women practiced the Bharni style (filled colors), Kayastha women often specialized in Kachni (line work), and women from marginalized communities developed the Godna style (dotted and tattooed motifs).

One of the least understood facts about Madhubani painting is that it wasn’t “discovered” by the art world until the mid-20th century. It existed in rural homes, on walls and floors, largely invisible to institutions and collectors. This invisibility is worth noting. An entire sophisticated artistic tradition flourished for centuries in the domestic sphere, practiced by women, never formally documented, never celebrated - until outsiders decided to look.

2. Where Did Madhubani Painting Originate?

Madhubani painting’s origin is rooted in the Mithila region, which geographically spans parts of Bihar in India and extends into Nepal. The most active center of production and the district from which the name derives is Madhubani in Bihar. But three villages became particularly associated with the tradition and its evolution: Jitwarpur, Ranti, and Rasidpur.

Jitwarpur is significant not just for historical reasons but because it was here that the pivotal transformation occurred. The madhubani art origin story typically cited is ancient - King Janak's wedding commission in the 8th or 7th century BCE. But the story that mattered for global recognition is recent. It dates to 1965.

That year, Bhaskar Kulkarni, an Indian government aid worker visiting from Delhi, arrived in Mithila with a radical proposal. Rather than allowing this art form to remain confined to ritual use on ephemeral walls, why not adapt it to paper? This idea seems obvious now. Then, it was a rupture. Kulkarni's intervention, supported by Pupul Jayakar (a cultural activist and historian working with the All-India Handicrafts Board), catalyzed a shift. The government provided artists with paper and colors at no cost, inviting them to translate their wall practice onto portable surfaces.

This was the moment Madhubani painting entered the larger cultural economy. This was when it became possible for rural women artists to sell their work beyond their immediate communities. This was when the tradition began its journey toward international recognition - a journey that would lead to Padma Shri awards, international exhibitions in Japan, Russia, Europe, and the United States.

3. Evolution of Madhubani Painting Over Time

The evolution of madhubani painting tracks two parallel histories: one of preservation and one of transformation. In madhubani painting’s history, this is the turning point: when a ritual practice learned at home had to adapt to paper, portability, and public visibility without losing its symbolic grammar. For centuries, the tradition remained largely stable - passed through women's hands, responding to the occasions that demanded it (weddings, births, festivals), using materials at hand (mud, natural pigments, simple tools). This stability was also constrained. The art form existed within rigid ritual boundaries.

Then came the droughts of the 1960s - natural calamity that created need, and with need, opening. When the Madhubani-to-paper initiative took hold around 1965-67, artists faced immediate practical adaptations. Brushes replaced fingers. Paper required different pigment mixtures than mud. The scale had to contract. But something else happened too: once the art form left the walls of a single household and entered the market, it became collectible. It became visible. Individual artists began to be named, recognized, awarded.

The history of madhubani art from the 1970s onward is inseparable from the women who pioneered this transition. Jagdamba Devi became the first female Madhubani artist to receive the Padma Shri, in 1975, for her meticulous work preserving authentic techniques while adapting to paper. Sita Devi (from Jitwarpur) received the Padma Shri in 1981; she was among the first to popularize the Bharni style on canvas, filling colors where traditionally only lines might have appeared.

Ganga Devi, received the Padma Shri in 1984. She specialized in the Kachni style (intricate line work) and created ambitious series like the Ramayana Paintings and her remarkable Manav Jeevan (Life of Mankind) series, which depicted the complete life cycle of a rural woman from birth through old age. When she was invited to represent India at the Festival of India in the United States in the 1980s, she didn't simply reproduce traditional themes - she began to experiment with fusion, blending Indian traditional form with Western elements.

This is the crucial evolution to recognize: modernization of Madhubani didn't corrupt it. It expanded it. Contemporary artists now address themes like women's empowerment, environmental protection, and social justice alongside eternal mythology. The subjects have multiplied, the mediums have diversified (canvas, paper, fabric, now digital), but the core visual language - the doubled lines, the filled spaces, the symbolic saturation - remains.

Key Characteristics of Madhubani Painting

1. Mythological and Religious Themes

Madhubani paintings are fundamentally concerned with the sacred. Hindu mythology provides the primary vocabulary: depictions of Krishna with Radha (divine love), Shiva with Parvati (cosmic union), Durga (warrior goddess), Lakshmi (prosperity and grace), Ganesha (remover of obstacles). In this sense, Madhubani sits within a much older continuum of Indian mythological paintings, where image-making functions as devotion rather than illustration.

The painting of mythological scenes serves a purpose beyond the aesthetic. When a woman paints Krishna stealing butter, when she depicts the marriage of Sita and Rama, when she renders Durga slaying the buffalo demon - she is not just illustrating a story. She is participating in a spiritual act. The painting becomes a conduit for the presence of the divine in the home. This is why characteristics of madhubani painting include such reverence for precision, for completeness, for fullness.

Religious themes often interweave with fertility symbolism. Paintings created for weddings (particularly Kohbar paintings for the nuptial chamber) combine mythological figures with explicit fertility imagery - Shiva and Parvati depicted alongside fish, turtles, and elaborate floral patterns. The sacred and the sensual are not separated; they are understood as aspects of the same cosmic principle.

2. Nature & Symbolic Motifs

Every creature and plant in a Madhubani painting carries meaning. The fish symbolize fertility and abundance - essential for wedding blessings. The lotus represents divine beauty, good fortune, and feminine power. Peacocks embody love, immortality, and peace. Elephants signify strength and prosperity. Bamboo, with its rapid growth and multiplication, represents lineage and masculine vitality. Parrots are love birds. Turtles symbolize the union of opposites (water and earth), hence the union of lovers.

The sun and moon mark cosmic cycles - longevity and the preservation of life. Even the trees chosen (tulsi, mango, coconut) carry symbolic weight in the Hindu cosmological framework. A river is never just water; it represents life force, purification, eternal flow. A tree is never just vegetation; it's the axis connecting earth to sky, roots to heaven.

This is what distinguishes Madhubani from merely decorative folk art where every choice carries intention. The natural world is read as a text and each element is placed with purpose. This is why they seem so visually dense - there is no empty space because every inch communicates.

3. Social Events

Beyond mythology, Madhubani paintings chronicle the domestic and social life of the Mithila region. Weddings are documented in elaborate detail, particularly in Kohbar paintings - the bride arriving in her palanquin, female family members attending, the groom waiting. Birth celebrations are recorded. Festival scenes show women gathered, work in progress, community ritual. Daily life - women grinding grain, tending fields, carrying water - becomes subject worthy of the same careful depiction lavished on divine figures.

This democratization of subject matter within Madhubani is significant. Sacred and secular share equal visual weight. A depiction of Krishna is not "more important" than a depiction of village women at work. Both deserve the same intricate treatment, the same density of pattern. This suggests a philosophy that sees the divine not as separate from daily life but as infused throughout it.

Contemporary Madhubani artists have expanded this social vocabulary further. Modern paintings now address women's education, reproductive rights, environmental concerns, and social justice. The tradition proves flexible enough to accommodate the artist's moment without abandoning its visual and spiritual core.

4. Cultural Significance

The cultural significance of Madhubani painting extends far beyond aesthetics. For centuries, it functioned as women's primary means of religious expression, creativity, and cultural transmission. In a society where women's voices were often circumscribed, Madhubani painting gave women agency - artistic, spiritual, and eventually economic.

The paintings were created for specific rituals. A Kohbar painting in the nuptial chamber was understood as essential for blessing the marriage with fertility and prosperity. Paintings created for births were believed to carry protective power. Those made during festivals were offerings of gratitude and invitations for continuing abundance. The paintings were not hanging in homes as art; they were functional sacred objects.

This is what makes the modern transition to commodity art complicated and interesting. When these ritual paintings entered the gallery market, they lost immediate ritual function. Yet something paradoxical occurred: by becoming collectible, by acquiring exchange value in the global art market, Madhubani painting gained preservation and visibility. Rural women artists gained economic independence. The tradition, threatened by modernization, was actually strengthened by it. This is the contemporary paradox at the heart of Madhubani's story.

5. Double Line Borders and Intricate Patterns

The double-line border is the visual signature of authentic Madhubani painting. Every composition is framed by double outlines - two parallel lines with the space between them filled with smaller marks: cross-hatching, dots, straight lines, or miniature patterns. This isn't a decorative edge; it's a philosophical statement.

The double line symbolizes duality and balance. According to Mithila cosmology, all existence manifests in pairs: masculine and feminine, earth and sky, creation and dissolution. The doubled line visually asserts this principle of complementary opposition. Where there is one line, there might be fragmentation. Two lines, separated and then bridged, suggest wholeness.

Within the painted surface itself, the space is never left empty. Figures are outlined in double lines, and the areas between these lines are filled with patterns - often cross-hatching or stippling. The background is equally dense: filled with flowers, birds, geometric forms, leaves. This absolute refusal of negative space is not a limitation but a strength. It creates visual intensity, perpetual movement, nowhere for the eye to rest - which is precisely the point. A Madhubani painting doesn't soothe through simplicity; it enlivens through saturation.

The intricate patterns themselves often mirror natural forms - fish scales, peacock feathers, flower petals - translated into geometric abstraction. A peacock becomes a complex interplay of circles and lines. A lotus unfolds as a geometric mandala. Nature is represented not realistically but symbolically, abstracted into the pure language of line and form.

5 Major Styles of Mithila Art Painting

1. Bharni Style

Bharni - meaning "filling" in Hindi - is the most visually exuberant of the Madhubani styles. Where Kachni emphasizes line, Bharni emphasizes color. The painter first outlines figures with bold black lines, then fills the enclosed spaces with vibrant, contrasting hues: brilliant blues, hot yellows, deep reds, electric greens, hot pinks, warm oranges. The resulting image pulses with chromatic intensity.

Bharni style was traditionally associated with Brahmin women of the Mithila region. Sita Devi, who popularized this style on paper and canvas in the 1970s-80s, became its most celebrated practitioner. Her works showed how completely the Bharni vocabulary could articulate Hindu mythology - gods and goddesses rendered not in the subtle tones of line work but in the full, almost overwhelming chromatic power of filled color.

What distinguishes Bharni is its emphasis on symmetry and intricate patterning within the filled spaces. A single garment on a divine figure might contain multiple colors, each color section containing its own geometric pattern. The effect is simultaneously busy and balanced, chaotic and harmonious.

2. Kachni Style

Kachni - the style of fine lines and minimal color - represents the opposite aesthetic philosophy. Where Bharni overflows with color, Kachni practices restraint. These paintings use one or two colors (classically red, green, or black) and rely entirely on intricate line work to create depth, texture, and meaning. Hatching, cross-hatching, stippling, dots, swirls - the entire tonal range is achieved through the manipulation of line alone.

Kachni was traditionally practiced by Kayastha women and represents a kind of visual asceticism. The monochrome palette demands that line work carry all the expressive weight. What might be conveyed through color contrast in Bharni must be conveyed through pattern variation in Kachni. This is why Kachni paintings often feel more delicate, more intricate, perhaps more psychologically subtle.

Ganga Devi, master of the Kachni style, proved this approach's aesthetic power through her extraordinarily detailed work. Her painting "Nag Panchami" (depicting snakes) transformed the subject into a labyrinthian maze of interweaving lines, creating a hypnotic visual experience through line alone. Kachni paintings have found particular resonance with contemporary viewers; their minimalist aesthetic seems oddly modern, a kind of traditional minimalism that predates 20th-century art movements by centuries.

3. Tantrik Style

The Tantrik style draws on tantric philosophical and spiritual traditions, incorporating symbols, mandalas, yantras (geometric diagrams representing cosmic forces), and sacred geometry. These paintings are less narrative than visionary - less concerned with depicting stories than with representing spiritual principles and energy.

Deities in Tantrik paintings - particularly goddesses like Kali - are rendered with mystical intensity, surrounded by symbols of spiritual power: chakras, sacred triangles, concentric circles, protective symbols. The color palette tends toward the earthy: black, white, red, ochre. The composition is often symmetrical, geometric, meditative. These are paintings meant for spiritual practice, for meditation, for the invocation of inner transformation.

What differentiates Tantrik Madhubani from other styles is its explicit connection to esoteric practices. While Bharni and Kachni tell stories and invoke blessings, Tantrik paintings function as visual mantras - objects of focused attention intended to facilitate spiritual awakening. The style appeals increasingly to contemporary practitioners of yoga and meditation seeking to understand the visual vocabulary of their spiritual practice.

4. Godna Style

Godna - derived from the Hindi word meaning "to prick, puncture, dot, or mark" - represents the tattooing tradition of Dalit and tribal women of Bihar. This style transforms body art into wall and paper art, borrowing the aesthetic vocabulary of tattoo design and applying it to Madhubani painting.

Where other styles employ color or elaborate line work, Godna uses monochrome simplicity: black ink, soot, or plant-based dyes applied in geometric, repetitive patterns. Concentric circles, dots arranged in grids, straight lines creating checkerboards, simple animal and floral renderings - these are the vocabulary. The style is minimalist by necessity and by conviction.

The significance of Godna extends beyond aesthetics into social history. Tattooing was a practice of marginalized communities. When women from these communities began translating their tattoo designs into painted form, they were literally reclaiming space within the broader Madhubani tradition. Godna paintings became artistic assertions of Dalit and tribal identity, turning what had been marked on bodies (often as markers of caste and community) into deliberate aesthetic choice and cultural pride.

Contemporary Godna artists work with graphite and ink, creating densely patterned compositions through stippling, hatching, and geometric repetition. The effect can be extraordinarily intricate and visually compelling - proving that color and complexity are not prerequisites for beauty.

5. Kohbar Style

Kohbar paintings are created exclusively for weddings, specifically painted on the walls of the Kohbar Ghar (bridal chamber) of newly married couples. These are the most ritually charged of all Madhubani styles, understood not as decoration but as sacred invocation of fertility, prosperity, and blessed union.

The central motif in classical Kohbar paintings is an elongated structure with two faces on either end - symbolizing the masculine and feminine energies uniting in marriage. This central form is often surrounded by six circles (representing the six circles of creation) and encircled by flora and fauna heavy with fertility meaning: lotus leaves, bamboo groves, fish, turtles, parrots, peacocks, snakes.

Each element carries ritual significance. The lotus leaf (upper section) represents the female; the bamboo grove (lower section) represents the male. The connecting stem represents the bond between them. Surrounding these central symbols are depictions of Shiva and Parvati (cosmic marriage), the sun and moon (eternal cycles), and often the bride and groom themselves, along with celebratory figures.

Kohbar paintings combine elements of both Bharni and Kachni styles - some areas filled with vibrant colors, others rendered in intricate line work. The overall effect is overwhelming in its symbolic density. These paintings are believed to carry transformative power - blessing the union, inviting fertility, ensuring a good sexual life and procreation. A Maithili groom traditionally worships the Kohbar painting before meeting his bride, making it the first sacred ritual he performs within the marriage covenant.

Madhubani Art Paintings FAQs

1. What is Madhubani art called?

Madhubani art is called by several names interchangeably: Madhubani painting, Mithila painting, Mithila art, and Mithila chitra. The term "Madhubani" derives from the district of Bihar where it originated; "Mithila" refers to the ancient kingdom in which the tradition flourished. Both names are correct; the choice between them often depends on whether one is emphasizing the geographic specificity (Madhubani) or the broader cultural region (Mithila). Their visual emphasis on order, balance, and cyclical patterning is also why Madhubani paintings increasingly appear as office wall paintings, where they function less as ornament and more as quiet symbolic anchors.

2. What is Madhubani famous for?

Madhubani painting is famous for several interconnected qualities: its vibrant color palettes and intricate geometric patterns; its absolute refusal to leave any space empty; its sophisticated symbolic vocabulary drawn from Hindu mythology, nature, and ritual life; its historical role as women's primary means of creative and spiritual expression in the Mithila region; and, increasingly, its global recognition as a major Indian folk art tradition. It's famous for being beautiful, complex, spiritually resonant, and the product of centuries of women's artistic knowledge transmission. Because of this visual richness and symbolic completeness, Madhubani paintings often translate well, as paintings for living room environments where narrative and cultural presence matter more than minimalism.

3. Who is the father of Madhubani Painting?

Madhubani painting doesn't have a single "father" because it emerged over centuries as a collective women's tradition. Among the artists themselves, Jagdamba Devi was the first to receive national recognition (Padma Shri, 1975), establishing her as the pioneering figure in the modern Madhubani movement. Other historical figures instrumental in bringing Madhubani to global recognition include Bhaskar Kulkarni (the government aid worker who proposed the paper transition in 1965) and Pupul Jayakar (the cultural activist and historian who supported this shift).

4. Which state is Madhubani painting from?

Madhubani painting originates primarily from Bihar, India, specifically the Madhubani district of the Mithila region in North Bihar. The tradition also extends across the border into Nepal, where the Mithila region continues geographically.

5. Who is the most famous Madhubani artist in India?

Several artists compete for this distinction depending on the criterion. Sita Devi (Padma Shri, 1981) is perhaps the most internationally recognized for her pioneering work bringing Madhubani to paper and popularizing the Bharni style globally. Ganga Devi (Padma Shri, 1984) is celebrated for her master-level Kachni work and innovative series paintings. Jagdamba Devi (Padma Shri, 1975) holds the distinction of being the first to receive national recognition.