What is Kalamkari Painting?

What is kalamkari? The word breaks down simply: kalam (pen, from Persian) and kari (craft or work). Pen-work. But to understand what kalamkari art is beyond translation, you need to see it as a process, not a product.

It's hand-painted or block-printed textile created entirely with natural dyes - every rust red from madder root, every indigo blue from fermented plant matter, every yellow from myrobalan flowers crushed and boiled. The traditional method spans twenty-three sequential steps: bleaching, mordanting with mineral salts, sketching with charcoal, resist applications, dye baths, river washing, sun-drying, and more washing. It's not efficient. It can't be. A single large piece might occupy an artisan for weeks.

in the contemporary sense means understanding this: each piece carries its maker's literal fingerprints in the slight variations of hand-drawn lines, the exact saturation of color achieved through patient layering, the way natural dyes shift and deepen as they age. It's the opposite of fast fashion - a textile practice rooted in sustainability, cultural memory, and the stubborn belief that objects should outlive the people who make them.

What's often overlooked is that authentic Kalamkari actually becomes more beautiful with age. Natural dyes develop patina. Synthetic dyes just fade in blotches. Browse through the rest of the blog to explore more Kalamkari painting information ranging from it’s origins to the materials used.

Kalamkari Painting History & Origin

1. Origin of Kalamkari Painting in India

The kalamkari painting origin stretches back further than most traditions care to admit. Archeologists found resist-dyed cloth fragments at Harappa - circa 2600 BC - proof that painted and dyed fabrics existed in the Indus Valley long before anyone called it Kalamkari. These weren't the Kalamkari we recognize today, but they're part of the lineage.

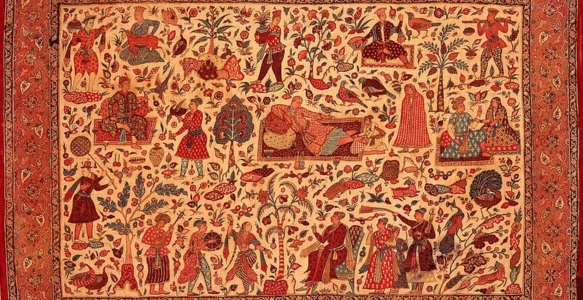

The kalamkari art origin in its recognizable form traces to the 8th century AD in Andhra Pradesh. Traveling musicians and painters - chitrakars - moved between villages narrating Hindu epics through large painted canvases. Think of them as oral historians who worked in dye instead of words. They were devotional tools, hung in temples during festivals, depicting Ramayana episodes, Mahabharata battles, scenes from the Puranas.

At first glance, the term "Kalamkari" sounds ancient, rooted in Sanskrit. It's not. The Mughals gave it this name - or rather, the Mughal courts encountered artisans practicing this craft in Golconda and along the Coromandel coast and called them Qualamkars. The modern word evolved from there. So understanding about kalamkari painting in its historical sense means recognizing this wasn't a sudden invention but gradual crystallization over centuries.

2. Evolution of Kalamkari Through Dynasties

During the Vijayanagara Empire (14th–17th centuries), Kalamkari flourished. It adorned temple chariots. It decorated palace walls. It created massive ritual scrolls. These were sacred objects, not commodities.

Then the Mughals arrived, and everything shifted. About kalamkari art during this period is really about transformation. The Mughal and Golconda sultanates saw the craft's commercial potential. Under their patronage - particularly in the Pedana region near Machilipatnam - Kalamkari absorbed Persian aesthetic influences: paisleys, botanical studies, geometric borders that spoke to Islamic design sensibilities.

The kalamkari painting history of the 16th through 18th centuries marks both the art form's apex and its first identity crisis. It expanded its visual vocabulary dramatically. Block-printing emerged alongside freehand painting, allowing scaled production without (yet) sacrificing quality. European courts started collecting it. Dutch, Portuguese, and British merchants grew wealthy trading it.

But the artisans themselves? Anonymous. Invisible in the economic chain.

Kalamkari art history took a dark turn during the colonial era. Machine printing rendered hand-painted textiles economically obsolete almost overnight. Synthetic dyes were faster, cheaper, more consistent. By the 1950s, only scattered communities in Srikalahasti and a few villages still practiced the full traditional method. The knowledge was bleeding out.

Then came 1956 - a pivot moment. Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay - India's pioneering handicrafts revivalist, first chairperson of the All India Handicrafts Board - journeyed to Andhra Pradesh with one mission: find the last surviving master of Srikalahasti Kalamkari and convince him to train a new generation. She found Jonnalagadda Lakshamajah. She succeeded. That single moment prevented the erasure of three millennia of accumulated knowledge. From that point forward, the tradition had a guardian. It had institutions. It had a deliberate path to revival instead of slow death by market forces.

Different Types of Kalamkari Painting

1. Srikalahasti Style

Srikalahasti is the freehand tradition - the most visibly "painted" of all Kalamkari styles. The artist works directly with a kalam (bamboo or date-palm pen), sketching outlines in charcoal first, then filling designs with natural dyes applied by hand. No blocks. No stencils. This allows for extraordinary fluidity and individual expression - no two Srikalahasti pieces are identical, ever.

Srikalahasti overwhelmingly depicts religious narratives. Scenes from the Puranas. Shiva and Parvati in cosmic union. Krishna lifting Govardhan mountain. Mahabharata battle sequences. Durga, Ganesha, Brahma rendered in jewel-like intensity. The color palette leans toward deeper tones: rich reds, blacks, indigos often against darker grounds.

The technique demands extraordinary skill. An artisan must understand color theory (how reds react to alum mordants, how blacks oxidize), understand the narrative well enough to improvise variations, and maintain hand precision across hours of meticulous work. A single large piece? Weeks, easily.

2. Machilipatnam Style

Machilipatnam Kalamkari (also called Pedana Kalamkari) employs block-printing - hand-carved wooden blocks pressed repeatedly onto fabric to create patterns. This isn't mechanization. The carving is entirely manual. The pressing is done by hand with careful attention to color saturation and alignment. But it does enable replication, consistency, faster production.

Machilipatnam's aesthetic differs markedly. Where Srikalahasti celebrates mythology, Machilipatnam embraces botanical narratives: intricate flowers, vines, creepers, birds in flight, trees laden with fruit. Persian influences are visible everywhere - paisley motifs, mehrab designs, geometric borders. These are secular subjects. The ground is typically light: cream or white, allowing the block-printed patterns to breathe.

Because blocks can be reused, Machilipatnam became the style adapted for fashion and home furnishings - the variant most likely to reach commercial scale while maintaining handcraft integrity. Yet it requires no less skill. The carving must be precise. Dye application must be even. Sequences must align perfectly or the pattern breaks.

3. Karrupur Style

Less widely known but equally significant: Karuppur Kalamkari, a Tamil Nadu tradition originating in the 8th century under the Chola dynasty, flourishing during Thanjavur's royal period. Karuppur represents a third distinct approach - hand-painted on silk and cotton using palm leaf and tamarind stick kalams, pens themselves distinct from Srikalahasti practice.

Karuppur pieces typically depict royal processions, temple scenes, episodes from epic literature, deities in courtly contexts. The visual result carries its own character: particular fluidity, particular color palettes, particular subject matter speaking to Thanjavur's aesthetic legacy.

Karuppur exists in acute danger. As of 2025, only one master artisan continues the full traditional practice. In 2021, Karuppur received Geographical Indication (GI) status - official recognition - but GI status without practitioners is just a memorial, not a living tradition. The art form's survival now depends entirely on whether the next generation chooses to learn what their elder knows. That's not a metaphor. It's literal.

Materials Used in Kalamkari Paintings

1. Natural Fabrics

Kalamkari begins with cotton - specifically, loosely woven cotton called gaada. Not dress fabric. Utilitarian, porous, capable of absorbing water and dyes deeply. The fabric gets washed thoroughly, then soaked in a paste made from myrobalan (a dried fruit rich in tannins) and buffalo milk. This preparation prevents color from spreading uncontrollably, infuses subtle sheen, primes fibers to accept and fix dyes.

Silk appears occasionally, particularly in Karuppur tradition, but cotton remains standard. Partly economic - cotton grows abundantly in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Partly aesthetic - cotton's absorbency allows for the subtle color variations and depth that characterize authentic Kalamkari.

2. Natural Dyes and Colors

Every color in traditional Kalamkari originates from plants, minerals, or fermentation:

Red emerges from madder root, manjistha, or cinnamon. Exact shade depends on dye bath duration, water mineral content, which mordant precedes it.

Yellow comes from myrobalan flowers (karakapuvvu), pomegranate skin, mango bark, turmeric solution. These yellows are notoriously fugitive in synthetic practice, but in Kalamkari - mordanted and aged - they develop remarkable stability.

Blue is natural indigo, vat-dyed in fermented baths. Indigo in Kalamkari carries depth synthetic indigo can't replicate - a slight greenish or purplish undertone.

Black comes from the most complex recipe: Kasim Kaaram, a blend of jaggery, rust-collected iron filings, and water, fermented until it reaches a dark mineral-rich liquid. Brushed onto fabric, it oxidizes to profound black.

Green isn't extracted - it's created through layering. Yellow first, set, then indigo over it. Greens from olive to emerald depending on proportions.

The mordant - alum, a mineral salt - fixes dye to fiber. Different mordants create different effects. This alchemy - understanding which mordant precedes which dye, which water quality affects which color - is knowledge that can't be learned quickly. It's embodied in the hands and eyes of artisans who've practiced for decades.

3. Tools Used in Kalamkari Art

The kalam is the defining tool. In Srikalahasti, it's a short length of bamboo or date-palm stick, sharpened into a nib, often wrapped with cotton to control dye flow. In Karuppur, palm leaf stems serve the same purpose. The kalam is primitive - but its primitivity is its intelligence. It can't hold large dye quantities, forcing deliberate strokes. It can't blur or blend, demanding precision. It creates line, not surface.

For outlining, artisans use charcoal sticks or burnt tamarind, which leaves fine, erasable lines on prepared fabric.

In Machilipatnam, wooden blocks replace the kalam - intricately hand-carved blocks functioning as both template and printing tool. These blocks take weeks to carve, representing immense capital investment.

River water - running water specifically - is essential for washing. Still water can't fully remove residual dyes and mordants. Sunlight is the final tool. Most drying happens under direct sun, which not only dries but helps "fix" colors, deepening saturation and permanence.

Themes and Designs of Indian Kalamkari Art

1. Mythological Figures

Temple-centered traditions - Srikalahasti, Karuppur - overflow with mythology. The Ramayana unfolds with Rama in exile, Sita's abduction, Lanka's siege. Mahabharata appears in battle scenes and dharmic tensions. Puranas provide vocabulary of gods and cosmic narratives.

Krishna appears frequently - dancing with gopis, lifting Govardhan, playing his flute while peacocks gather. They're theological narratives, repeated endlessly because meaning deepens with each retelling. When an artisan paints Krishna for the hundredth time, they're meditating on essence - what gesture, color, expression must communicate to a devotee.

Goddesses appear with particular prominence: Durga slaying the buffalo demon, Lakshmi in lotus splendor, Parvati beside Shiva. The Tri Devi representing the cosmic feminine principle.

When you explore paintings of south india, you encounter this devotional vocabulary repeatedly - figures that are symbolic, iconic, stylized, more concerned with theological truth than visual accuracy.

2. Floral Patterns

Particularly in Machilipatnam and secular variants, floral motifs dominate: roses, jasmine, tulips, chrysanthemums rendered with botanical precision yet decorative intent. They're idealized, symmetrical flowers functioning as design elements.

Vines wind through compositions. Leaves rendered with vein structure attention. Fruit trees laden with mangoes, pomegranates. This floral vocabulary reflects Persian influence (garden as paradise metaphor) and local aesthetics - flowers familiar to artisans and patrons in South Indian gardens.

It's tempting to see these as merely decorative. But in the context of folk art paintings, they carry symbolic weight - nature as both sacred and aesthetic, botanical and mythological forms coexisting.

3. Animal Figurines

Peacocks appear more frequently than any other animal - the bird sacred to Hinduism, symbol of cosmic energy and divine grace. They're rendered with extraordinary plumage attention, often in profile with tail feathers fanned in full display.

Elephants signify royal power, gravitas. They appear in procession scenes, as deity attributes. Lions and tigers occasionally appear as power symbols, particularly in royal commissions. Birds in general - cranes, parrots, eagles - populate floral scenes and mythological narratives.

4. Geometric Patterns

Mandalas - concentric circles, geometric patterns radiating from centers - appear frequently, particularly in borders and backgrounds. These aren't purely decorative. They carry metaphysical significance, representing cosmic order and spiritual unity.

Paisleys (teardrop botanical motifs) appear in Persian-influenced pieces, arranged in symmetrical repeating patterns. Cones, diamonds, abstract geometric designs create structure and visual rhythm. These elements fill space, create continuity, guide the eye - but they also serve ritual function. The repetition of geometric form is meditative, deliberately mathematical in ways that mirror cosmic order.

Contemporary collectors often discover Kalamkari through office wall paintings - these geometric patterns translating well to modern interiors while maintaining traditional integrity.

Kalamkari exists at a crossroads. Fewer than ten percent of young artisans in rural Andhra Pradesh express interest in continuing the craft. The knowledge threatens to disappear with each master who retires.

And yet. A new generation of consumers - fatigued by fast fashion, searching for meaning in material objects, awakening to sustainability - are discovering it. When you explore indian art paintings, you encounter collectors valuing these not as decorative elements but as heirlooms. Luxury designers collaborate with artisans. Museums mount exhibitions. The Ministry of Textiles launched the Swadeshi Campaign to promote handcrafted Indian textiles.

To encounter authentic Kalamkari is to see, embedded in fabric's surface, someone's hands, someone's breath, someone's sustained attention across weeks.

That conversation - three thousand years old - has nearly been lost. But it's not over yet.

FAQs About Kalamkari Paintings

What is special about Kalamkari art?

Kalamkari is exceptional for its marriage of technical complexity and spiritual intentionality. Every color originates from nature - zero synthetic shortcuts.Most importantly, Kalamkari can't be rushed or industrialized without losing its essence. A single large piece requires weeks or months of sustained attention. In a world of mass production, slowness is what makes it unique.

What is another name for Kalamkari?

Kalamkari is sometimes called "pen-work" (direct translation) or regionally by place of origin: Srikalahasti Kalamkari, Machilipatnam Kalamkari, Karuppur Kalamkari. In Tamil Nadu, particularly Karuppur tradition, it's also known as Chithira Paddam ("picture trace" in Tamil). Historically, the Mughals called artisans practicing this craft Qualamkars, from which "Kalamkari" evolved.

Why is Kalamkari expensive?

Kalamkari's cost reflects actual value, not artificial scarcity. The 23-step process requires days or weeks per piece. Each step demands precision: fabric preparation can't be rushed, dyes must be sourced (often from distant regions), color application requires steady hands and patient layering, extensive washing is non-negotiable for permanence. Most critically, few artisans practice authentically, so demand vastly exceeds supply. A single master artisan produces perhaps a dozen major pieces yearly.

Which pen is used for Kalamkari art?

The kalam - a pen fashioned from bamboo or date-palm stick, tapered to fine nib, often wrapped with cotton - is the traditional tool. They're simple, handmade, individualized to each artisan's grip and preference. A kalam can't hold large dye quantities, can't blur or blend, can't move faster than the artisan's hand allows. This limitation is the strength - it enforces deliberation.

How long is the process of a Kalamkari painting?

The full traditional process involves 23 sequential steps, typically requiring one week to several months per piece depending on complexity and size. Small pieces (short dupatta, framed study) might complete in 10–14 days. Larger narrative-heavy pieces (full saree, wall hanging) often take 6–12 weeks or longer. Each step must be completed fully before the next begins: fabric preparation, sketching, dyeing, washing, drying, additional dyeing, additional washing, final finishing all demand specific timeframes.