Who Was Nandalal Bose?

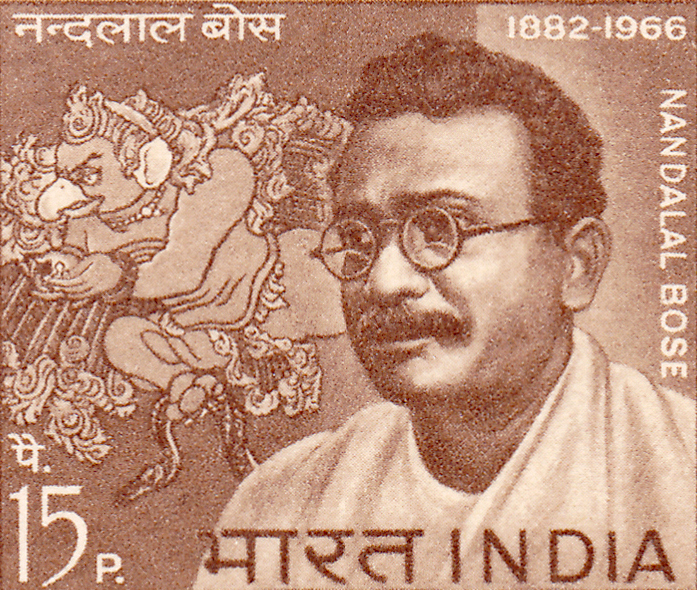

Nandalal Bose (1882–1966) was a pioneering modern Indian artist, teacher and thinker, and one of the central figures of the Bengal School of Painting. Born at Haveli Kharagpur in present-day Bihar to a Bengali family, he moved to Calcutta as a teenager and eventually defied family expectations to study art at the Government School of Art, where he became a key disciple of Abanindranath Tagore.

His early training drew him towards Indian miniature painting, the Ajanta and Bagh cave murals, and Japanese wash techniques. Over time, these influences fused into a distinct Nandalal Bose style of painting: lyrical, disciplined, steeped in myth and village life, and quietly political. He rejected academic naturalism imported from Europe, aligning himself instead with a movement to reclaim Indian visual traditions within a modern framework.

A verifiable detail that anchors his journey: in 1921, Rabindranath Tagore invited him to head Kala Bhavana, the art school at Santiniketan, a role he held for decades. This matters, because it placed him at the centre of an experimental campus where art, craft, theatre and music were woven into daily life - and allowed him to shape generations of artists who would define modern Indian art.

By the time of his death in 1966, Nandalal Bose’s work was not just a personal practice; it had become a language through which India imagined itself - on walls, in posters, and even in the illustrated pages of the Constitution.

Art Styles Used by Artist Nandalal Bose

Nandalal’s practice was never trapped in one medium. His search moved across ink, colour, printmaking and murals, often returning to the same themes in different forms.

1. Ink & Brush

In his later years, Nandalal Bose turned increasingly to monochrome ink and brush, creating spare works inspired by East Asian Sumi-e painting. These compositions - boats, birds, trees, a gust of wind suggested with two or three strokes - were stripped to essentials, with vast areas of untouched paper.

A work like The Boats (often translated as The Boat or related to the mood of Floating a Canoe) shows this clearly: a few fluid lines describing vessels on water, signed simply “Nanda”. The economy of means is deliberate. What’s often overlooked is how this phase completes a circle: the artist who once studied Ajanta’s dense frescoes moves, in old age, to a kind of visual haiku.

For many viewers used to richly detailed figurative paintings, these ink works are almost a test of attention. How much feeling can a single line carry?

2. Woodcuts

Woodcut and relief printmaking gave Nandalal Bose a robust, tactile language that could travel beyond elite circles. Influenced by Japanese prints and local craft practices, he carved scenes of rural life, myth and labour, using bold contours and flattened forms.

Woodcuts allowed for multiple prints from a single block, making Nandalal Bose’s art accessible in a way oil painting rarely is. This democratic impulse is not incidental. It aligns with his engagement with the freedom movement and the Swadeshi call to value indigenous techniques, materials and audiences.

At first glance, these prints can seem almost folkish. Look closer and the sophistication of the carving, the rhythms of black and white, the placement of empty space reveal a modernist discipline at work.

3. Temperas

In the earlier phases of his career, especially during the Bengal revivalist years, Nandalal frequently worked in tempera - pigments mixed with a binding medium, often applied on paper or board.

Paintings like Sati belong to this phase: mythological subjects rendered with the luminous colour and fine detailing associated with the Bengal School. The tempera surface allowed him to combine miniature-like precision with broader, mural-inspired compositions.

This is also where his training under Abanindranath Tagore is most visible: the subtle gradations, the flattened perspective, the use of motifs like lotuses or flames to carry symbolic weight. Yet even here, his figures often feel anchored in lived emotion, not just in literary reference.

4. Watercolors

Watercolour was perhaps his most versatile medium. . For anyone exploring watercolour paintings as a medium today, Nandalal Bose offers a reminder that transparency and restraint can be as dramatic as saturation and detail. Nandalal adopted the wash painting technique - layering thin, translucent passes of colour - to create soft, atmospheric images that became a hallmark of the Bengal School.

Whether in depictions of rural festivals, river banks, or deities like Annapurna, his watercolours often balance gentle tonal washes with decisive linear drawing. In Annapurna (1943), for instance, a vivid field of orange is set against a cool cerulean disc around the goddess, while line differentiates the flowing grace of the goddess from the more skeletal male figure beside her. The work moves between abstraction and storytelling, between colour field and narrative.

For anyone exploring watercolour paintings as a medium today, Nandalal Bose offers a reminder that transparency and restraint can be as dramatic as saturation and detail.

5. Linocuts

The stark, black-and-white linocut became one of Nandalal Bose’s most powerful tools for political imagery. His print Bapuji (Dandi March), created in 1930, shows Mahatma Gandhi striding forward with his staff, the figure carved in rhythmic lines against a bare ground.

Linoleum is softer than wood, allowing quick, expressive carving. Nandalal used this to his advantage, producing images that were both graphic and deeply human. The linocuts could be printed and circulated widely, aligning with nationalist efforts to create strong, recognizable icons of resistance.

In some sense, these linocuts are the sharpest intersection between Nandalal Bose’s art style and the urgencies of his time.

Famous Paintings Of Artist Nandalal Bose

Below are key works and motifs, useful context if you’re learning how to collect, research, or buy art online with confidence.

1. Haripura Posters

The Haripura Posters are perhaps the most cited example in discussions of Nandalal Bose, though they are technically a sprawling series rather than a single work. Commissioned by Mahatma Gandhi for the 1938 Indian National Congress session at Haripura, Gujarat, Bose and his students created nearly 400 panels depicting villagers - potters, hunters, musicians, bull wranglers - in vibrant, simplified forms.

Rendered in a style drawing from Kalighat pata and folk idioms, these posters lined the pandal and gates, bringing everyday rural life to the centre of a national political gathering. The quiet radicalism here lies in subject matter: it is the farmer, the worker, the woman at her household tasks who become protagonists of a political vision.

2. Sati

Among Nandalal Bose's famous paintings, Sati holds a special place. Created in the early 20th century, it reimagines the mythological figure of Sati - who self-immolates in response to her father’s insult to Shiva - through the lens of devotion, sacrifice and moral complexity.

The painting uses techniques associated with the Bengal School: careful wash, fine line, a controlled palette, and flattened space. Art historians have read it as both a spiritual image and a metaphor for the sacrifices demanded during India’s struggle against colonial rule. It’s tempting to think of Sati as purely historical, but its ethical questions about duty and self-erasure still echo uncomfortably today.

3. Shiva Drinking Poison (Samudra Manthan)

Nandalal’s treatment of Shiva Drinking Poison, drawn from the Samudra Manthan episode, fits within his larger engagement with mythological themes as living allegories. While specific versions vary, works on this subject typically show Shiva with the halahala poison held at his throat, his calm absorbing collective danger.

Here, his style tends to balance classical references - ornament, iconography - with a sober, almost austere handling of form. In the context of his time, the image of a deity absorbing poison can be read as a metaphor for the burdens of leadership and the costs of holding conflict within oneself.

4. Bapuji (Dandi March)

Bapuji (Dandi March) may be the single most widely reproduced Nandalal Bose painting. Created as a linocut in 1930, it shows Gandhi mid-stride, leaning slightly forward into the future, the staff almost an extension of his spine.

The print is dated “12.4.1930” and inscribed “Bapuji” along the lower margin - a precise historical anchor. That date matters: it ties the work to the actual moment of the Salt March, turning the image into both documentation and emblem. The composition’s stark contrast and fluid lines compress the vastness of the movement into one distilled gesture of walking.

5. Floating a Canoe

Works related to boats - such as The Boats - appear across Nandalal’s oeuvre, especially in his later ink and wash paintings. Floating a Canoe is often used to refer to this family of images that show small vessels against large expanses of water and sky, rendered with a few confident strokes.

These paintings, influenced by Japanese Sumi-e, carry a sense of solitude and motion that feels far from the crowded nationalist canvases of Haripura. The boat becomes a small, persistent presence on a vast surface - perhaps a quiet metaphor for the individual within collective history.

6. Birth of Chaitanya

Nandalal’s interest in Vaishnava themes and devotional figures surfaces in works depicting Chaitanya, the 15th–16th century saint associated with ecstatic devotion to Krishna. In paintings and drawings on the Birth of Chaitanya, the artist often emphasizes tenderness and sanctity within domestic space.

A related work, his Untitled (Caitanya and Haridas), shows Chaitanya with Haridas, a Muslim-born devotee, foregrounding spiritual kinship over social hierarchy. In the broader context of Nandalal Bose paintings description, these works underscore his preference for narratives where spiritual intensity coexists with everyday human relationships.

7. Annapurna

Annapurna (1943) is a striking watercolour that stages a dialogue between nourishment and asceticism. The goddess Annapurna - provider of food - is framed by a cerulean disc, her body drawn in flowing, harmoniously proportioned lines. Beside her stands a more skeletal, almost flayed male figure (often read as Shiva), held within a field of orange.

Formally, the painting plays with two chromatic and conceptual planes: earthly sustenance and spiritual transcendence. The ArtFlute insight here is this: looking at Annapurna today, one can see how Nandalal quietly anticipated later debates about hunger, scarcity and dignity in India - not through overt commentary, but through the way he staged two bodies in uneasy relation.

8. Arjuna as a Warrior

Nandalal returned often to the Mahabharata and to Arjuna in particular. In works like Parthasarathi and related compositions, he renders the tense space of the Kurukshetra battlefield and the charioteer-guide relationship between Krishna and Arjuna.

Images of Arjuna as a warrior tend to highlight not just his martial prowess but his moment of doubt - the instant before action, when he questions the cost of war. For Nandalal Bose’s art, this hesitation is crucial: heroism is not a static pose but a troubled, ethical decision.

Nandalal Bose Contribution To Art In India

1. Role At Kala Bhavana Shantiniketan

When Nandalal Bose took charge of Kala Bhavana in 1921, Santiniketan was still an experiment - a school under the open sky, where Tagore envisioned an education rooted in Indian soil yet open to the world. Nandalal helped translate that philosophy into visual art.

He encouraged students to study folk crafts, village festivals, and rural architecture, treating them as sources of form and meaning rather than “primitive” curiosities. Murals, stage design, posters, idols for campus celebrations - all became part of the curriculum. Art was not confined to framed pictures; it spilled into the rhythms of institutional life.

Many of his students - Benode Behari Mukherjee, Ramkinkar Baij, among others - would go on to become major figures of modern Indian art, carrying forward and transforming his teachings. The ripple effect is hard to overstate: much of what is now taken for granted as a modern yet rooted Indian visual culture was rehearsed at Santiniketan under his watch.

2. Influence On Future Indian Artists

Nandalal Bose’s influence on future Indian artists works on several levels.

Stylistically, he demonstrated that it was possible to evolve a modern idiom out of Indian sources - Ajanta, folk pata paintings, miniatures, East Asian brushwork - without mimicking European realism. This encouraged later artists to mine their own contexts with confidence, from narrative painters to those working in more abstract modes.

Institutionally, his role as a teacher and principal modelled an expanded idea of what an artist could be: a pedagogue, designer, collaborator in national projects. After independence, his team’s illustrations for the Constitution of India and his design of the national emblem’s artwork helped weave art directly into the fabric of the Republic.

His work suggested that modern Indian art could attend to both myth and politics, village and city, without collapsing into propaganda or mere decoration. For contemporary artists navigating tradition and global discourse, that remains an instructive tension.

FAQs About Nandalal Bose Biography

1. What is Nandlal Bose best known for?

Nandalal Bose is best known for pioneering a distinctly Indian modern art idiom, his leadership at Kala Bhavana in Santiniketan, and his iconic works such as the Haripura Posters and the linocut Bapuji (Dandi March). He is also widely recognized for illustrating the original manuscript of the Constitution of India and shaping the Bengal School’s wash-based Nandalal Bose art style.

2. What art style is Nandalal Bose known for?

Artist Nandalal Bose is primarily associated with a modern adaptation of the Bengal School style - using wash techniques in watercolour and tempera, simplified forms, and motifs drawn from Indian mythology, rural life and folk art. Over his career, he also became known for expressive ink and brush works, woodcuts and linocuts, each extending his search for a rooted yet contemporary visual language.

3. What is Nandalal Bose's contribution to modern Art?

Nandalal Bose’s contribution to modern art lies in how he fused Indian artistic traditions with modernist sensibilities, helping define the very idea of “modern Indian art”. Through his teaching at Santiniketan, his nationalist imagery, and his integration of art into public and constitutional spaces, he created a model where aesthetics, ethics and cultural self-definition are in continuous conversation.

4. What are the famous works of Nandalal Bose?

Some of the most famous paintings of Nandalal Bose include Sati, the Haripura Posters, Bapuji (Dandi March), Annapurna, and various depictions of mythological subjects like Shiva, Chaitanya and Arjuna. His later ink works of boats, birds and landscapes are equally celebrated for their minimalism and quiet intensity, expanding what a Nandalal Bose painting can mean beyond grand narrative scenes.

Works of the masters like Nandalal Bose, Jamini Roy and M. F. Husain are great picks for office wall paintings, offering sophistication and timeless presence.