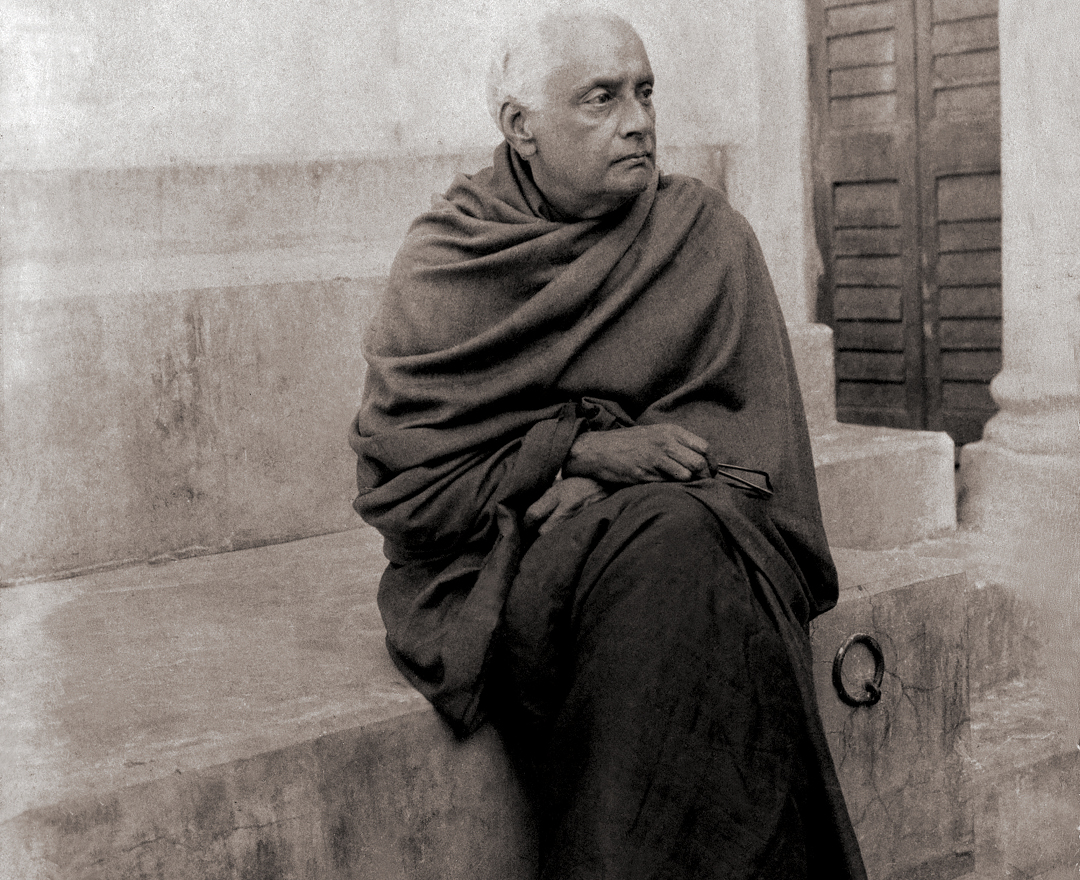

Who Was Gaganendranath Tagore

1. Early Years and Family Influence

Born 18 September 1867 into the Jorasanko household, Gaganendranath inherited a world already dense with creative assertion. His father Gunendranath, his brother Abanindranath, his uncle Rabindranath - already ascending toward literary celebrity - his sister Sunayani Devi, herself a painter of consequence.

What's often overlooked is that Gaganendranath worked in theatre - designing sets and costumes for his uncle's dramatic productions, even acting in performances. This theatrical background would prove crucial later, embedded in the compositional logic of his caricatures and the stagecraft of his compositions. The family did not immediately expect him to become an artist in his own right. In 1907, when his son died, painting became not a career path but a form of survival - the activity that kept him tethered to the world when the world no longer made sense.

2. Artistic Education and Training

Gaganendranath received no formal art education from institutions. Instead, he trained under Harinarayan Basu, a watercolourist then principal of Calcutta's Government School of Art, who taught him technique and encouraged experimentation. More transformative, though, was the encounter with Japanese aesthetics beginning around 1906-1910. Through the Tagore circle and Japanese artists sent by philosopher Okakura Kakuzo, Gaganendranath absorbed the logic of sumi-e (Japanese ink painting): the idea that empty space matters as much as mark-making.

Gaganendranath absorbed this entirely. His illustrations for his uncle's autobiography Jeevansmriti (1912) reveal this influence flowering: rich dark tones set against delicate washes, a visual economy where nothing is wasted. The technique was Japanese but the sensibility - responding to loss, to the landscape of grief - was entirely his own.

Artistic Style in Gaganendranath Tagore Paintings

1. Spiritual Motifs

From around 1911 onwards, Gaganendranath became fixated on spiritual and religious imagery. Rather, something more private, more interior. The Chaitanya series (1911-1915) stands as his most sustained work in this vein - based on the sixteenth-century saint Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and his ecstatic devotion. These paintings depict moments of divine rapture, rendered primarily in black ink against luminous gold backgrounds.

What's striking is the emotional intensity held in formal restraint. A figure bends in ecstasy; light pools around them. The work carries what one critic described as "the mark of a soul wronged with sorrow," yet there's nothing sentimental about it. The restraint prevents that. The Pilgrims works extend the same spare language into scenes of wandering devotion. These works emerge as visual autobiography: Gaganendranath was not painting devotion abstractly but searching for a visual language to contain his own spiritual confusion.

2. Satirical and Caricature Art

Around 1915-1916, something shifted. The withdrawal from his brother's nationalist idealism led Gaganendranath toward something far more corrosive: social satire. Beginning in 1917, he published Birup Bajra (Strange Thunderbolt) and Adbhut Lok (Realm of the Absurd) - bound collections of black-and-white drawings that constituted perhaps his most vital contribution to Indian visual culture. These works target the hypocrites of his era: zamindars posturing as patrons while exploiting peasants, maharajas whose authority has been hollowed by colonial rule, clergy dispensing purification for profit, and above all, the aspiring babu class - Anglicized professionals sweating beneath Western suits, desperate to be mistaken for sahibs.

The caricatures operate through exaggeration and symbolic substitution. A greedy priest becomes a bloated demon; a government puppet transforms into an automaton spouting words from invisible hands. One caption riffs on the humiliation of trying to pass as a sahib - and being reduced to babu anyway. The wit here cuts deep. What distinguishes these from mere cartoons is their formal sophistication. The line work is masterly - bold, economical, expressive. A few strokes establish character. The compositions feel theatrical, almost stage-like in spatial economy.

3. Cubist Paintings & Abstract Forms

At an age when most artists settled into mastery, Gaganendranath began experimenting with Cubism. His first cubist paintings appeared in the journal Rupam in 1922, accompanied by art historian Stella Kramrisch's influential essay "An Indian Cubist," which positioned Gaganendranath as modernism's pioneer in India. These paintings featured flattened planes, jagged edges, overlapping forms.

Unlike European Cubism treating abstraction as an end, Gaganendranath used cubist fragmentation to depict mythological and spiritual subjects - legendary cities, temples, sacred mountains. His House of Mystery series (1922) exemplifies this. These paintings create an ambiguous interior space - partitions, doors, windows, shafts of light, pools of shadow - producing an effect simultaneously claustrophobic and dreamlike.

Between 1920 and 1925, he developed increasingly abstract compositions using intersecting colour planes and fragmented perspectives to suggest the essence of sacred places rather than their appearance. Dwarkapuri and Swarnapuri (both 1925) - cubist watercolours imagining the legendary cities of Krishna's mythology - use jagged geometric forms to create a visual equivalent of spiritual transcendence. After 1925, his post-cubist work turns austere: colour recedes, line takes over. These late works, made before a stroke paralyzed him in 1930, remain among the most enigmatic paintings in modern Indian art - an approach that clarifies Gaganendranath Tagore’s painting style as neither imitation nor simple abstraction, but a tool for making the unseen felt.

Famous Paintings of Gaganendranath Tagore

1. The City in the Night

Gaganendranath explored nocturnal urban scenes extensively from around 1916 onwards - works depicting Calcutta's rooftops, dimly lit streets, solitary figures emerging from shadow as if viewed through a veil. These paintings use dramatic chiaroscuro (that play of light and dark) to transform familiar landscapes into mysterious, almost dreamlike spaces. The influence of both Japanese ink painting and European Expressionism is evident in the restrained palette: blacks, greys, warm ochres creating mood and atmosphere rather than detail. The works suggest the visual disorientation of the modern city - what's visible only partially, what remains hidden, how urban experience fragments consciousness itself.

2. Pratima Visarjan

Pratima Visarjan (1915) ranks among Gaganendranath's most beloved works, and for good reason. The title refers to the immersion of Durga's idol at Puja's conclusion - that climactic moment when the goddess who has "visited" her earthly parents for four days must return to her celestial abode. Most artists might treat this as documentary scene. Gaganendranath captures its emotional turbulence instead: the luminescence of proceedings, light playing on water, solemnity mixed with abandon as devotees accompany the goddess to her ritual farewell. The painting pulses with colour - bold strokes, vibrant greens and blues, the glow of torches - yet maintains formal dignity, preventing the scene from becoming merely festive. The work synthesizes his mastery of light effects with his capacity to render collective emotion without descending into sentimentality.

3. Dwarkapuri

Dwarkapuri (1925) represents Gaganendranath's mature cubist vision. The legendary city of Krishna becomes here a shattered vision rendered in watercolour through fractured planes and jagged geometric forms. The painting does not depict Dwarka as it might have appeared, but rather as a kind of spiritual essence compressed into cubist space. Blues, greens, warm oranges fracture and recombine, suggesting both the sacred geography of mythology and the disorienting spatial logic of modernist vision. The achievement lies in that synthesis - a work that could only be made by someone fully schooled in European modernism yet rooted in Indian tradition.

4. Chaitanya Series

The Chaitanya series (roughly 1911-1915) stands as Gaganendranath's most sustained meditation on spiritual ecstasy and devotion. These are not narrative paintings but attempts to visualize interior states - the moment of divine rapture, communion between guru and disciple, the ego's surrender before the infinite. Rendered primarily in black ink against luminous backgrounds (usually gold or light tan), they create an effect of illumination from within. The figures - sometimes just silhouettes, sometimes rendered with delicate detail - seem to dissolve into light. Composition remains invariably spare: a few figures, vast empty space, bold calligraphic brushstrokes. There are echoes of both Japanese sumi-e painting and Indian miniature traditions, yet the emotional register is entirely modern - psychological, introspective, existential. What strikes viewers is the restraint. No melodrama, no ornament. The power lies in what is suggested rather than stated.

5. Satirical Caricatures

The satirical works - collected in portfolios like Birup Bajra (1917) and Adbhut Lok (1917) - represent Gaganendranath at his most socially engaged and visually inventive. These black-and-white drawings function as both visual arguments and formal experiments. Their subjects are the hypocrisies of colonial and post-colonial Bengali society: zamindars, maharajas, clergy, government officials, anglicized professionals. The caricatures employ exaggeration, symbolic substitution, and theatrical framing to expose the gap between social pretense and actual character. One cannot overstate their formal sophistication. The line is always purposeful, composition always clear. A single figure may dominate the frame, silhouetted against suggestion of space. Props - crown, ledger, ceremonial object - become weapons of satire. The titles amplify the wit: the whole assemblage feels like scenes from surreal farces staged by someone who understood both theatre and politics.

6. House of Mystery

House of Mystery (1922) is perhaps Gaganendranath's most haunting cubist work, existing in multiple versions. These paintings create an ambiguous interior space - partitions, doors, windows, shafts of light, pools of shadow. The effect is claustrophobic and dreamlike simultaneously. Cubist fragmentation here does not serve abstraction but rather mystery: the more the form fractures, the more the space becomes unknowable, suggesting presences one cannot quite see. Some versions appear theatrical - stage sets for surreal drama. Others feel almost like X-rays of interior consciousness, revealing the hidden geometries of an imagined space. The work testifies to Gaganendranath's conceptual sophistication. He understood that Cubism could become a tool for expressing the psychological and the mystical, not merely the formally innovative.

7. Princely India

Gaganendranath's satirical works critiquing the maharajas and zamindars of colonial India constitute a thematic category unto themselves. His caricatures of "Princely India" - the feudal order transformed into mere theatre by colonial rule - rank among his most biting social critiques. These works depict maharajas whose authority has been hollowed by colonial subjugation, zamindars whose wealth has become obscene in a starving landscape, and nobles whose empty pomp barely conceals their irrelevance. The visual strategy remains consistent: exaggeration, symbolic distortion, stark black-and-white formal clarity that amplifies the critique. What distinguishes them from simple mockery is the presence of something like sorrow - a recognition that people are trapped in systems that corrupt them, that the hypocrite is himself a victim of colonial modernity.

8. Temple in the Mountains

Temple in the Mountains (1922-1925) combines cubist fragmentation with Indian sacred architecture. A solitary temple nestled amid majestic peaks is deconstructed into geometric planes and angular forms. Rather than rendering the temple naturalistically, Gaganendranath uses intersecting lines and fragmented surfaces to suggest the essence of the sacred place - its soaring aspiration, its integration with cosmic grandeur, its isolation. The colour palette remains restrained: soft blues, greys, touches of warm ochre. The effect is both modernist and deeply spiritual: the cubist form becomes a vehicle for expressing the transcendent quality of the sacred site. This work exemplifies how Gaganendranath adapted European modernism to Indian subject matter without falling into regionalism or exoticization.

9. Bed of Arrows

Bed of Arrows (1922), also known as Bhishma, depicts one of the Mahabharata's most charged moments - the ancient warrior Bhishma Pitamaha lying mortally wounded on a bed of arrows after being struck by Arjuna, yet refusing to leave the battlefield until the war concludes. Gaganendranath renders the scene with striking geometric angularity and a muted palette of greys, browns, and dull reds. The figure of Bhishma is central, rendered with bold jagged lines suggesting both the arrows penetrating his body and the fragmentation of his consciousness as he approaches death. The composition has a cubist quality - multiple spatial registers, fractured forms - yet never loses sight of the human drama: the paradox of heroic resignation, the strange dignity of chosen suffering. The work operates on multiple registers: as narrative illustration of mythological epic, as meditation on sacrifice and suffering, and as formal experiment in cubist composition.

10. Morning Star

Morning Star demonstrates Gaganendranath's mastery of light, atmosphere, and the suggestion of spiritual dimension through painterly means. An ethereal dawn scene rendered in watercolour, the painting presents a serene landscape illuminated by the soft glow of the morning star. Two small figures walk along a road rendered luminous by moonlight and starlight. The composition is reductive - minimal detail, vast sky, a sense of infinite space suggested through the play of light and tone. Yet there is nothing abstract about it. Rather, the painting achieves what critics call a territory "between realism and impressionism" - a space where the visible world becomes transparent to something beyond itself. The work exemplifies the late phase of Gaganendranath's artistic vision, when he had moved beyond the decorative aspirations of early modernism toward something more austere and profound. Morning Star suggests spiritual wandering, a pilgrimage through darkness toward the promise of dawn.

Common Themes in Gaganendranath Artworks

1. Urban life and modernity

The shock of colonial modernity - trains, electricity, Western fashion, bureaucratic systems, capitalist logic arriving in traditional Indian cities - created a kind of cultural vertigo that Gaganendranath felt acutely and registered with precision. His urban paintings and caricatures capture this vertigo. Works like Calcutta Roof Tops capture the fragmentary vision of the modern city, rendered with impressionistic technique suggesting the visual chaos of urban experience. His satirical works, particularly Adbhut Lok and Birup Bajra, train their scorn on the figure of the Anglicized babu - the English-speaking professional whose adoption of Western dress and manners is figured as a kind of social death, a loss of authentic identity.

Yet Gaganendranath's critique is not nostalgic, neither does he condemn it or call for return to an imagined past. Rather, he registers the genuine disorientation that modernity produced, the way traditional hierarchies were simultaneously reinforced and destabilized by colonial rule. His urban paintings suggest cities transformed by light, movement, and fragmentation - modernist visual languages deployed to register modernist experience. Even his cubist works, ostensibly abstract, often depict urban or architectural spaces fractured and reassembled through multiple viewpoints.

2. Spiritual symbolism

Gaganendranath understood spirituality as an interior state, a mode of consciousness that exceeds rational comprehension. His spiritual paintings - the Chaitanya series, the Pilgrims series, his temples and sacred mountains - attempt to visualize the invisible. They do so through restraint: by removing ornament, by using vast empty spaces, by fragmenting form in ways that suggest transcendence of individual perspective. The spiritual works reveal Gaganendranath's deep engagement with Indian religious traditions on a philosophical rather than merely devotional level. The saint Chaitanya interests him not as a figure to be venerated through conventional iconography, but as an embodiment of spiritual ecstasy - the moment when the self dissolves into something larger.

These are not sentimental works. They make formal demands on the viewer, ask for contemplation rather than immediate emotional response. In this way, Gaganendranath's spiritual paintings prefigure modernist and even abstract art, using form and emptiness as vehicles for exploring consciousness itself. The spiritual and the formal are inseparable in his work.

3. Social inequality and hypocrisy

The satirical works reveal a political consciousness running deep through Gaganendranath's entire oeuvre. He was not a propagandist or didactic artist. Rather, he understood that satire - the exposure of gaps between claim and reality, appearance and essence - is itself a form of formal sophistication. His caricatures of zamindars, maharajas, clergy, and colonial officials function as weapons of critique operating through wit, exaggeration, and symbolic distortion. They expose how power operates through performance, how authority depends on costume and ritual, how those without genuine power most desperately ape the gestures of those possessing it.

What distinguishes Gaganendranath's satirical vision from mere mockery is the presence of something like sorrow. A critic notes that his caricatures are "not the soured delineations of a cynic but scenes which must have wronged the artist's soul with sorrow." There is a kind of tenderness in the exposure - a recognition that people are trapped in social systems that corrupt them. This ethical dimension - the refusal of cruelty even in the act of critique - elevates his satirical work above cartoon into something approaching genuine art.

4. Impact of colonial rule

All of Gaganendranath's satirical work, and much of his spiritual work as well, emerges from meditation on how colonial rule transforms a society - not simply politically and economically, but aesthetically and spiritually. The zamindars and maharajas in his caricatures are not evil men; they are men whose actual power has been hollowed by colonial subjugation, whose response is to adopt empty gestures of authority, to become automata speaking words written by invisible hands. The English-speaking Bengali professional sweating beneath his Western suit is not simply ridiculous; he is a man trapped between worlds, unable to inhabit either authentically.

Gaganendranath's response to this condition is not nostalgic nationalism (that was more his brother Abanindranath's path) but rather artistic experimentation that refuses to stabilize or resolve the contradictions of colonial modernity. His cubist paintings, satirical works, and spiritual paintings all suggest a consciousness fractured and multiplied by the experience of living within an empire, of seeing one's own culture through colonized eyes. This is what makes him distinctive: not a resistance artist but an artist of contradiction, someone who refused easy answers.

What makes Gaganendranath exceptionally relevant today is that he refused the false choice between tradition and modernity - not through compromise but through genuine synthesis. His cubist paintings of mythological cities, his satirical drawings of colonial subjects, his spiritual paintings rendered through modernist abstraction all represent an artistic honesty about what it meant to be an Indian artist in the early twentieth century. That same negotiation - between local and global, traditional and contemporary, spiritual and formal - remains the central challenge for artists working in India. To look at Gaganendranath is to see a model of how that negotiation might be conducted with both aesthetic rigor and emotional authenticity, without collapsing into either parochialism or rootlessness. This is why discussions of Gaganendranath Tagore art style still feel urgently contemporary: it names a practice built from contradictions, held together by discipline.

To look at a Gaganendranath Tagore painting is to witness a moment when form becomes transparent to something beyond itself. Perhaps it is the luminous empty space surrounding a saint in ecstatic devotion. Perhaps it is the geometric fragmentation of a sacred mountain rendered in watercolour. Perhaps it is the satirical exaggeration of a colonial official's blank face. In each case, the artist refused easy meaning. He demands instead that we sit with ambiguity, with the fractured and multiple nature of consciousness under colonial modernity. That refusal remains the painting's gift to us. When we encounter such works in collections, we recognize them as real art paintings - not representations of idealized beauty, but documents of an artist thinking visually about impossible conditions, and finding formal solutions that still astonish. Many of his most contemplative pieces were rendered in watercolour paintings, a medium that suited his philosophy of restraint and luminosity. There's something about standing before a Gaganendranath in a gallery - whether hung above a wall painting for living room or in a museum space - that returns you to something you didn't know you'd forgotten: that art can ask questions without demanding answers. And once you begin mapping Gaganendranath’s paintings across periods - spiritual ink works, caustic satire, cubist interiors - you start to see how a Gaganendranath Tagore artwork is less a single style than a sequence of courageous pivots, each one a new answer to the same question: how does an artist stay honest inside an era built on performance?

Gaganendranath Tagore Biography FAQs

1. Why is Gaganendranath Tagore remembered?

Gaganendranath Tagore is remembered as a pioneering modernist artist who introduced cubism to Indian painting and created some of the most incisive social satire produced in the early twentieth century. He is valued for his refusal of easy nationalist revivalism and his insistence on artistic experimentation as a response to colonial modernity. His satirical caricatures remain powerful critiques of social hypocrisy and the psychological damage inflicted by colonialism. More broadly, he demonstrated that Indian artists could engage with European modernist forms not as imitators but as innovators, creating original syntheses of Eastern and Western aesthetics.

2. What is the name of the cartoon of Gaganendranath Tagore?

Gaganendranath created several celebrated cartoons and satirical portfolios. His most famous sets are Birup Bajra (Strange Thunderbolt) and Adbhut Lok (Realm of the Absurd), both published in 1917. Later, he published Naba Hullod (Reform Screams) in 1921. These were collected as bound portfolios of black-and-white satirical drawings critiquing the hypocrisy and colonial mimicry of Bengali society. The Modern Review also published many of his cartoons beginning in 1917.

3. Why is Gaganendranath Tagore important in Indian art history?

Gaganendranath Tagore was one of the earliest modern artists in India and the only Indian painter before the 1940s to seriously experiment with cubism. More broadly, his work reveals what modernism looks like when deployed outside European contexts. Rather than treating Western avant-garde forms as foreign impositions, he used them as tools to articulate specifically Indian concerns - spiritual yearning, social critique, and the psychic fragmentation produced by colonial rule. His influence extended to the institutional level: he co-founded the Indian Society of Oriental Art (1907) with his brother, which published the influential journal Rupam and helped establish frameworks for discussing modern Indian art. His approach - blending European techniques with Indian subject matter and philosophical concerns - established a model that subsequent Indian modernists would follow. Works like his feature in major collections, displayed alongside what might be considered the finest cubist paintings from the global canon, remain a defining reference point when discussing Gaganendranath Tagore’s famous paintings and their place in Indian modernism.

4. Is Gaganendranath Tagore related to Rabindranath Tagore?

Gaganendranath was the nephew of the poet Rabindranath Tagore. Rabindranath was Gaganendranath's uncle - the brother of Gaganendranath's father Gunendranath. Gaganendranath illustrated several of Rabindranath's works, including his autobiography Jeevansmriti (1912) and various short stories. Rabindranath also established the Bichitra Club at the Tagore residence in 1915 with Abanindranath as first teacher and Gaganendranath as first director, later becoming its driving force. The relationship between uncle and nephew was one of mutual respect and creative exchange, though they pursued somewhat different artistic paths. This association with Rabindranath has occasionally overshadowed Gaganendranath's independent achievement, yet his contributions to both spiritual and formal innovation remain distinct and substantial.